The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time begins in childhood. Specifically, Link’s childhood. At the start of the game, the camera pans down to a sleeping boy clad in green. He is the only one of the Kokiri (forest children), who does not have a fairy. That is until Link is visited by the the persistent sprite Navi, who wakes him up and sets him off on a grand adventure. He meets the Princess Zelda who, despite her youth, is the only one who foresees the danger presented by the visiting King Ganondorf’. Ganondorf plans on breaking into the Sacred Realm through the Temple of Time in order to steal the Triforce, an ancient artifact which is said to have the power to grant wishes. Zelda, with Link’s help, hopes to head off Ganondorf by acquiring the Triforce first, as a way to protect Hyrule.

These two children fail.

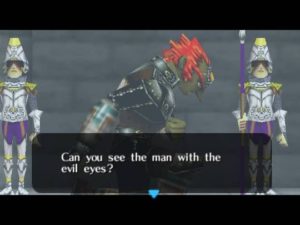

Image Source: Vizzed.com

It may seem strange to look at The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, with all of its sweeping grandness and see how it relates to my life, but I couldn’t help but find multiple parallels as I played through it for Speculative Chic’s 2017 Resolution Project. A lot of this has to do with the fact that this is not the only time I’ve played this now classic game. I first picked up Ocarina of Time when I was a geeky thirteen-year-old, who, in the classic narrative of geeky thirteen-year-olds, was awkward and struggled to fit in. It was hard not to look at young Link, the boy without a fairy, and almost see a kindred spirit. And just like Link, I ended up failing too. Despite really enjoying Ocarina of Time, I never completed it.

In all fairness, it wasn’t actually my game. Sure, I owned an Nintendo 64 (a luxury I remember being shocked that my parents would ever buy for my brother and me), but the game itself belonged to a friend’s older brother who had already made some serious headway into the game. I began my own file, progressed through the beginning, completed the first dungeon, and meet up with Princess Zelda. But ultimately, even if I had owned a copy, there was pretty good chance that my adolescent self would have lacked the patience to get much farther (The Water Temple would have destroyed me). Instead, I spent most of my time running around Hyrule and dying a lot. And when I discovered that I could access the owner’s save file, I never looked back. Here, not only could I explore, but I could do so on the back of a horse.

Image Source: Playbuzz.com

After returning the game, my life was mostly free of the influence of Link, Zelda, and Ganondorf for years. At least until I met my future husband in college, who loved to play (and replay) The Zelda Games. Throughout the course of our relationship, I’ve watched him play Twilight Princess, Skyward Sword, Wind Waker, and of course Ocarina of Time. I found myself in a strange position. Even though I had never finished a Zelda game myself (unless you count the ridiculously fun Hyrule Warriors), I had become a bonafide fan of the franchise. So when our Editor-in-Chic announced The Resolution Project for 2017, finally taking the time to play through Ocarina of Time made perfect sense.

But of course, the game looks a little different when played through adult eyes.

After failing to protect the Triforce from Ganondorf, Zelda is whisked away on horseback by her body guard, Impa. Link, inside the Temple of Time, is catapulted forward seven years into the future. When he awakens, he discovers that he has grown up. As a child, he wasn’t old enough to take on Ganondorf. But as an adult, he is ready, much like I was finally ready to beat the game.

See what I said about finding parallels to my own life?

Image Source: Zeldadungeon.net

Because of the time travel aspect, the game is divided into two unique parts, each with their own flavor. Sure, Link faces significant dangers as a child — from killer spiders to a snotty fish princess — but it’s all done with almost a playful air. When you speak to local townsfolk, they cheerfully comment on your ongoing “adventure.” Your weapons (a slingshot, a boomerang) aren’t all that different then children’s toys (let’s just ignore the very sharp sword). The tone is often light, which is further enhanced by the wide variety of entertaining side missions you can accomplish that run the gambit from selling masks to catching chickens.

But when Link is thrust into adulthood, he faces a very different Hyrule. The capital, once full of smiling people and shops, has been destroyed by the reign of Ganondof, the buildings now charred remains, and the streets filled with the moaning undead. A dark cloud covers Death Mountain, your childhood home is filled with carnivorous plants, and Lon Lon Ranch, once run by the lazy Talon who loved his chickens, is now headed by a jealous man who — Talon’s daughter infers — beats the horses.

Image Source: Planetminecraft.com

That’s not to say that the later portion of Ocarina of Time is overly dark. This is a game made for all ages, after all. But Link’s adulthood is a time period where the stakes are much higher, and all actions have consequences.

Fortunately, these aren’t usually bad consequences. As adult-Link, the darkness of Ganondorf is slowly wiped away as you progress through the game, meaning you really get to see the impact of your actions. Similarly, in the real world adulthood may be marked by greater challenges and responsibilities, but it also comes with its fair share of rich rewards. As a child, I didn’t have to worry about earning a salary or paying a mortgage, but adulthood comes with so much more freedom. You don’t have to live under the watchful eye of your parents, and you’re allowed to select and progress a career that’s truly meaningful for you. In Ocarina of Time, adult-Link tackles more complex, and challenging dungeons, utilizes a larger variety of weapons (that are nothing like child’s toys), and defeats greater threats. This includes Ganondorf himself. As a child, you fail in your quest to protect the Triforce and The Sacred Realm. As an adult, you save the day.

It’s what makes the ending of Ocarina of Time so bittersweet. After Ganondorf (or Ganon, as he is eventually known) is truly defeated, you and Zelda are transported to a clear blue sky filled with clouds. Here, Link learns that he must put the Master Sword to rest, and return to his original timeline where he will “regain (his) lost time” and grow up the way he is “supposed to be.”

Image source: Amino Apps.com

I find Zelda’s dialogue to be particularity heartbreaking in this scene. Because Link isn’t the only one whose childhood ended the day Ganondorf entered the Scared Realm. Zelda’s did just as quickly, only without the benefit of a seven year nap. Instead, she watched her home destroyed, and Hyrule twisted under the reign of Ganondorf, with the knowledge that it was all her fault. Earlier in the game, Zelda tells Link, “The flow of time is always cruel… Its speed seems different for each person, but no one can change it… A thing that doesn’t change with time is a memory of younger days.” While these words were originally spoken under different circumstances (Link’s realization that his friendship with Saria cannot be as it was when they were children), they take on new meaning in this scene. Zelda’s childhood will never be returned to her, so perhaps she sees restoring Link’s as a kindness.

But is it, really? Aren’t the benefits of adulthood enough to make weathering the burdens worth it? Is the flow of time always cruel?

The resolution to Ocarina of Time might seem strange at first, but this is not the first time in the game that Link finds himself pulled back to his own childhood. The Master Sword within the Temple of Time creates a bridge between the two timelines, allowing you to travel back and forth as often as you’d like. In fact, Link must travel back multiple times in order to beat the game. Link’s final journey back to childhood is a mere continuation of this, even though it ends up feeling much more sorrowful. Link (or Zelda for that matter) can not be part of the celebration that occurs in wake Ganondorf’s defeat. Not with his own missed childhood sneaking back up on him to collect their stolen years.

Image Source: Nintendooceanv3.kif.fr

Playing Ocarina of Time from the perspective of an adult comes with other consequences too, especially when it comes to specific characters. Many people have complained about Zelda’s inescapable role as the damsel in distress, which I can relate to. As an adult, Zelda masquerades herself as the enigmatic Sheik, jumping in frequently to teach Link lessons and the necessary songs to warp from place to place. But the moment Zelda puts away Sheik’s rags for her own pink dress, she is forced back into her traditional role in the narrative, that of the captive princess. This is an aspect that has come to wholly define her, despite the fact that she is otherwise a far more interesting character. I can’t help but find this a tragedy.

Image Source: Vizzed.com

Ganondorf, on the other hand, is far from a complex character (at least in this particular Zelda Game), although he is a real threat to Link and Hyrule, making him effective as a villain in other ways. Unfortunately, Ganondorf — a black man (the only black man in the game in fact) — represents multiple negative racial stereotypes. At first, he is a thief, and by the end of the game, he is also a black man who abducts a white girl. And while I hesitate to bring in western concepts to a game that was made by a foreign country (Japan) during an era when the world was a little less aware of racial complexities, but it did make me uncomfortable at times.

Playing The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time as an adult was a truly enjoyable experience. You can really see why this game is praised as being one of the best (if not THE best) in the Zelda series. Ocarina of Time manages to be challenging, without making me want to quite the game in disgust (although my frustrations with the boss Bongo-Bongo brought me pretty damn close to that. I never really got the hang of archery). The story and characters are truly engaging, and the game is structured well, with lengthy puzzle laded dungeons broken up by smaller, more lightheaded side quests. Finishing Link’s journey as an adult really opened my eyes to different the layers presented in this highly influential game. Ocarina of Time may be my first Zelda game, but I can already tell that it won’t be my last.

I frigging love this game. :3

It’s such a classic