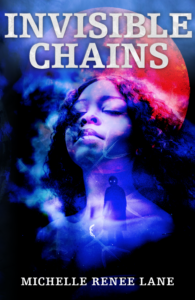

At Speculative Chic, we feature a lot of authors who share everything from their favorite things to the inspiration for their work. But why not also share their fiction? Welcome to Fiction Friday, where you’ll be able to sample the fiction of a variety of authors, including those who write at Speculative Chic! Today, we’re featuring Michelle Renee Lane, whose name you may recognize from her deep dive into race and horror here at Speculative Chic, including “With This Ring: You’ll Be Dead: Violence Against Female Protagonists in Vampire Fiction.” What you shouldn’t forget, however, is that Michelle is also a published author, whose debut novel, Invisible Chains, was nominated for a Stoker Award, and today, we’re giving you sneak peak between the pages!

About the Book

Invisible Chains (2019)

Invisible Chains (2019)

Written by: Michelle Renee Lane

Genre: Historical Horror/Dark Fantasy

Pages: 359

Publisher: Haverhill House Publishing

Jacqueline is a young Creole slave in antebellum New Orleans. An unusual stranger who has haunted her dreams since childhood comes to stay as a guest in her master’s house. Soon after his arrival, members of the household die mysteriously and Jacqueline is suspected of murder.

Despite her fear of the stranger, Jacqueline befriends him and he helps her escape. While running from the slave catchers, they meet conjurers, a loup-garou, and a traveling circus of supernatural freaks. She relies on ancestral magic to guide her and finds strength to conquer her fears on her journey.

Currently Available from: Haverhill House Publishing || Amazon || Barnes & Noble || IndieBound || Target || Walmart

Invisible Chains Excerpt

Chapter 1

A hurricane nearly destroyed the plantation the day I was born. Moman Esther was in labor for half the night. She took shelter in the slave quarters, but the wind and rain rocked the shack right off its foundation. Great torrents of water soaked her skin until she thought she might drown. She claims the storm came just as her waters broke. I don’t know if that’s true, but my emotions and the weather have always seemed connected.

“Your first word was ‘magic’,” she told me.

Moman taught me everything she knew about our ancestors and the religion they’d passed down to her. Most children learn to count to ten and how to recognize the letters of the alphabet, but my first lessons were about the gods and goddesses of Vodun. It’s hard to raise a child with your own beliefs when you’re a slave, but Moman managed to do just that. She was a strong woman. I wanted to be just like her — smart, beautiful, brave, and powerful. Plantation life will use up your body and stomp your dreams right out of your heart if you let it. The trick is not to let life beat you down — no matter what.

Life isn’t a fairytale. My story isn’t about a prince rescuing a princess, and there aren’t any happily ever afters. No goblins, trolls or dragons here, but there are plenty of other monsters.

***

Charlotte was Master’s daughter. So was I, but since Moman was a slave, my birth didn’t matter much to him beyond my value at auction. Master called his favorite little girl Lottie. That man spoiled her every chance he got. He never gave me a second glance except to ask for more biscuits. Like all his other bastards, I was invisible to him. I wish Lottie had ignored me, too, because at some point she got it into her head we were rivals. I had less than nothing, so why she felt jealous of a slave was beyond me. I don’t know what injustice she imagined I’d committed against her, but for as long as I could remember, she loved to hate me.

We grew up together in rural Louisiana pretending we weren’t related. My eyes should have been enough proof. They were the same dark blue, almost violet, as Lottie’s. Master’s wife hated me even more than my half-sister did. I was a constant reminder of her husband’s infidelities. He had children with at least three other slaves besides Moman, so Lottie had a bunch of half-brothers and sisters. None of them got to spend as much time alone with her as I did. They were lucky.

Lottie received a new book of fairy tales for Christmas one year — couldn’t have been more than four or five — and she wanted to pretend to be every princess and damsel in distress. She read to me so that we could play together. In her versions of the stories, she was the most beautiful princess that had ever lived.

“When do I get to be the princess?”

She laughed when I asked to wear the crown of daisies. “Who ever heard of a pickaninny princess?”

She was always cruel, but I refused to shed a single tear over her. I wanted to be the princess. I yearned for my happily ever after. I didn’t care if I had to sleep for a hundred years; I longed for the love of a handsome prince. I would have settled for being Le Petit Chaperon Rouge, but I was always Le Grand Méchant Loup.

Lottie refused to hear my protests. She didn’t care if it wasn’t fair. She always got the lead role.

“How do you know there aren’t any pickaninny princesses?”

“Because there aren’t any in this book.” Lottie poked her finger at the cover.

The Vodun gods and goddesses were better than any old storybook princess, but I wasn’t allowed to talk about them. Moman would use pictures of Catholic saints to represent the gods and goddesses on a shelf in the pantry, behind the flour, where she hid her altar — St. Peter for Damballah, Lazarus for Papa Legba, St. Expedite for Baron Samedi, and her favorite, Our Lady of Lourdes, for Erzulie Dantor. It was no coincidence that this hardworking dark-skinned woman who sought vengeance against those who tried to steal her power was our household goddess.

“We’re pretending to be princesses. Dragons and ogres aren’t real, either. Why can’t I be the princess sometimes?”

“Well, you just can’t. I’m always the princess.”

I wanted to wear the crown of daisies even though breathing fire would have proven more useful. Moman wouldn’t have to work so hard to get the stove lit first thing in the morning if I was a dragon.

I sat with my back to Lottie, arms folded tightly against my chest as she kicked me and screamed at me to accept a lesser role in our game of makebelieve. I ignored her as best I could until she finally gave in. Knowing I had won, no matter how small the victory, was worth every scrape and bruise her shoe buckles left on my shins.

“Fine. You can be the princess just this once, but don’t go getting all high and mighty.”

I put on the daisy crown and pretended to be Cinderella. She was my favorite. Cinderella was treated almost as bad as a slave before her fairy godmother cast the magic spell she needed to win the prince and escape her life of servitude. Not to mention that Lottie was a natural at playing one of the evil stepsisters.

Life would’ve been so much easier if I looked like a fairytale princess. At least that’s what I believed until we both got a little older. Lottie had more freedom than me — she could read, write, play, eat when she was hungry, sleep when she was tired — but she was the daughter of a rich white man who made sure to keep her in line. Our father decided what books she could read, what she learned (or didn’t) in school, and who she could or couldn’t marry. Marriage for most women wasn’t much different than slavery, except the children of rich white women didn’t get sold off like livestock. On the plantation, Lottie witnessed the same horrors as me, but while I would hide my face and cry, she would scramble to get a better look with a big smile on her face. If princesses behaved like her, I’d rather be a dragon any day.

***

Moman worked in the house, which gave me access to the family mansion, the gardens, and best of all, the kitchen. She and I shared a mattress in the pantry, stuffed with clean, earthy-smelling straw. Warm in the winter, and cool in the summer.

On spring mornings before the birds woke, warm breezes brought in the comforting smells of sweet magnolia trees, mingled with the musky scent of sweating slaves working in the fields.

Moman wasn’t born a slave. Before her Créole daddy died of yellow fever, he taught her and his other children how to read. When Grandfather died, Grandmother had no way to prove she and her children were free. White folks didn’t even recognize their marriage, because Grandmother had been a slave when they met. He never petitioned for her manumission, so it was only his word that had given her freedom. Grandmother was sold at auction. So were her children. They never saw each other again.

After Master bought her, Moman kept her education a secret. Feigning ignorance kept slaves alive. Moman had other secrets, too. She practiced the old ways, and she was the only Mambo for miles around. So, when she taught me how to grow herbs, make biscuits, build a fire, and collect eggs, she also taught me conjuring. She would draw vévé in the ashes beside the hearth, and taught me how to call upon the loa at night after all the work was done.

Her skills went beyond basic root work and charms. She taught me to take my dreams seriously too, because sometimes hers would come true. If I had a nightmare, she’d make me tell her as much as I could remember, and then she’d write it down in her spell book. From the time I could walk, I’d had nightmares about a man with pale skin, haunting green eyes, and a shock of dark wavy hair. He was always dressed in black and surrounded by shadows, so I could never quite make out his other features. I didn’t dream about him every night, just often enough to make Moman worry. Somehow, I knew he was from another time, and from a faraway place. Bad things happened when he was around, even though he never hurt me. No matter how many times I dreamt about that man, I would always wake up screaming.

Along with my education in magic, Moman taught me how to read, too. By the time I was ten I could read most of Lottie’s schoolbooks, and I stole copies of L’Abeille de la Nouvelle-Orléans and Harper’s from the burn pile. I’d hide them under our mattress with Moman’s spell book and would sneak off to read them behind the woodshed near the swamp. Cottonmouths and black widows kept me company under the cypress trees as I read every scrap of paper I could find. Nobody wanted to linger by the woodshed longer than necessary, so it was a perfect hiding place. I read about slave auctions in New Orleans, dry goods for sale, birth announcements, engagements, obituaries, stories about yellow fever outbreaks, runaway slaves, and everything else deemed fit to print. But I liked fairytales best.

Moman was proud of me, but she warned me never to show off my abilities in front of Master and his family. They’d make an example out of me. I’d get a whipping for sure, or worse. Smart slaves kept their mouths shut about their hidden talents, or they became dead slaves.

While Lottie learned how to play piano, sing, dance, and run a household full of slaves, all I wanted to do was read, write, and work spells. My chores — wood to chop, water to fetch, laundry to hang, rugs to beat, windows to clean, eggs to gather, and lots of other work — kept me busy from sun up to sun down. It was hard to find an excuse to hide behind the woodshed, but it was easy to sneak off on the days when Lottie’s tutor was around. Michié Henri was almost handsome with his dark golden wavy hair, and funny little wire-rimmed glasses that kept you from guessing what color his eyes were behind the thick lenses. He came on Tuesday mornings after breakfast and would spend an hour teaching Lottie grammar. In the afternoons, she practiced music. Lottie took a fancy to Michié Henri, and gave him her undivided attention during those lessons. Lottie’s mother made it known she did not approve of this infatuation and stayed close by to make sure it never went any further than “juvenile flirtations”. It didn’t matter how nice or smart Michié Henri was, he didn’t make enough money to marry into her family. In her book, a lowly teacher was not much better than a servant.

One day, during Lottie’s lessons, a fire broke out in the kitchen.

“Mamzèl, come quick!” Moman was coughing and gasping for breath when she ran into the house.

“Come here, girl,” Lottie’s mother said, and snapped her fingers at me.

I put down my rag and the silver fork I was polishing in the dining room and hurried to her side. Her mouth was set in a stern straight line as she stared down at me.

“I need you to be my eyes and ears, understand? I want you to tell me everything that happens in this room while I’m gone.”

“Yes, Mamzèl.” I bowed my head and took her place next to the settee.

She hurried off to help with the fire and left me to stand guard over her daughter’s chastity. Shortly after her mother left the room, Lottie made her move. She professed her love for Michié Henri in a poem. When she was done reciting the flowery and somewhat inappropriate words, he faked a cough and tried his best not to laugh. A knot formed in my stomach and I held my breath as I watched a dark shadow pass over Lottie’s face. Moman used to say that girl had the Devil in her. I could almost believe it when she got angry and her face changed so suddenly. All the color drained from her skin and her flesh shifted into an expressionless mask, blank as a clean sheet of parchment. Michié Henri was not as rich as Master, but he was raised in polite society and acted like a gentleman. He respected the feelings of others.

“Mademoiselle Charlotte,” he said, “I am truly flattered, but I am engaged to a young woman in the next parish over. I’m sure another lucky young man will soon find himself bewitched by your beauty.”

Lottie’s face turned deep red. She was never denied anything she wanted, and she wanted Michié Henri. He stopped smiling, though, once he saw how angry she was. She glared at him, clutched her dress at the collar, and ripped it downwards. A pale pink nipple peeked out from under the torn cloth.

“What…what are you doing? Have you gone mad?” Michié Henri tried to stop her from doing any further damage to her clothes. She just kept staring at him with that look of hatred in her eyes and grinned, baring her teeth like a rabid dog. And then she screamed.

“Help! Someone, please!” She made tears fall from her eyes then turned to me and said one word: “Run.”

I did as I was told and went to find Mamzèl. By the time we got back to the study, Lottie’s older brother, Jimmy, had the tutor on the floor. Poor Michié Henri tried to protect his head as Jimmy kicked away at his ribs and ground his heel into his groin. He begged Jimmy to stop. As his pleas got louder, Jimmy stomped and kicked harder.

“What is going on in here?” Mamzèl demanded.

“Oh, Maman,” Lottie cried. She wrapped her arms around her mother’s waist and winked at me. “Monsieur Henri tried to…I can’t even say the words. All I did was read him a poem I wrote, and he went wild.” Lies and cruelty came easy to Lottie. “Ask Jacqueline, she saw the whole thing.”

“Is this true, child?” Mamzèl glared down at me, arms tightly folded across her chest. Jimmy stopped his assault. I felt like the last piece of brambleberry pie at a late summer picnic. All eyes were on me.

“Speak up, girl.” Lottie made sure I was looking at her when she spoke. She knew I was afraid of her, but if I said what she wanted me to say, I’d be lying to her mother. Lottie was scary, but her mother was a force of nature. If I lied to Mamzèl and she found out, I’d get a whipping. If I told the truth, her daughter would find far worse ways to punish me.

I thought back to the morning I’d caught her killing newborn chicks in the hen house when I went there to collect the eggs. She’d met my look of shock with a devious grin.

“They’re just dumb animals. Who cares what happens to them?”

“They’re helpless little babies, Mamzèl Lottie. How can you hurt something that’s done you no harm?”

“Don’t tell my mother or I’ll tell her it was you.” She ran off laughing and left me to clean up their limp, soft, yellow bodies. One little chick was still clinging to life. I put it out of its misery by breaking its neck. Later, I told Moman and she made me swear never to tell anyone about it.

“If Lottie finds out it was you who told, what you think she gonna do to you? Les Blancs think we’re no better than beasts in the field. She sees no difference between you and those chicks.”

Moman was right. Something was wrong with Lottie, and if I made her mad, no one would come to put me out of my misery. I wished I could speak up, tell the truth, and save Michié Henri, but I wasn’t a princess, and I was no dragon. I was just a little black girl with no voice and no power. The threat of violence kept my mouth shut.

“Yes, Mamzèl. It’s just like she said. I saw the whole thing. Michié Henri grabbed her and tore her dress. I ran as fast as I could to find you.”

Michié Henri lay on the floor and stared up at me, his eyes so wide I could see more white than blue, like the look hogs get on their faces just before slaughter. I felt sick to my stomach. His mouth fell open, but no words were coming out. He rarely paid much attention to me, but he was never unkind. I’d lied to save my own skin. I wanted to feel guilty, but he could leave the plantation whenever he wanted. I couldn’t. He might be badly beaten or crippled when he left, but he could still leave.

“That’s all for now, girl. Go help Esther in the kitchen.” Mamzèl’s lips curled up at the corners in what I could only guess was her attempt at a smile. I went to help Moman clean up the mess from the fire. Before I left the study, I took one last look at Michié Henri lying on the floor pleading for his life. I was glad it was him and not me about to get the beating of a lifetime. I went about my business and wondered if he’d leave the plantation in a casket.

About the Author

Michelle Renee Lane writes dark speculative fiction about identity politics and women of color battling their inner demons while falling in love with monsters. Her work includes elements of fantasy, horror, romance, and occasionally erotica. Her short fiction appears in the anthologies Terror Politico: A Screaming World in Chaos, The Monstrous Feminine: Dark Tales of Dangerous Women, The Dystopian States of America, Graveyard Smash (July 2020), and Dead Awake (forthcoming). Her Bram Stoker Award nominated debut novel, Invisible Chains (2019), is available from Haverhill House Publishing.

Michelle Renee Lane writes dark speculative fiction about identity politics and women of color battling their inner demons while falling in love with monsters. Her work includes elements of fantasy, horror, romance, and occasionally erotica. Her short fiction appears in the anthologies Terror Politico: A Screaming World in Chaos, The Monstrous Feminine: Dark Tales of Dangerous Women, The Dystopian States of America, Graveyard Smash (July 2020), and Dead Awake (forthcoming). Her Bram Stoker Award nominated debut novel, Invisible Chains (2019), is available from Haverhill House Publishing.

No Comments