They might not be raindrops on roses or whiskers on kittens, but that doesn’t mean that we love them any less. Welcome back to My Favorite Things, the weekly column where we grab someone in speculative circles to gab about the greatest in geek. This week, we sit down with Tim Major, whose had not just one, but TWO books come out this year! First up is Snakeskins from Titan Books, and second up is his short story collection, And the Houselights Dim, from Luna Press Publishing.

What does Tim love when he’s not writing creepy science fictional thrillers? Spoiler alert: Tim’s a bit of a cinephile and has some unique offerings to share with us today. Interested? Read on to learn more!

Films are important to me. I adore lists of all-time favorite films, but instead of any attempt at being comprehensive, here are six films (or film sequences) that I happen to love right now.

The Films of Karel Zeman

Admittedly, I’ve seen only four of this Czech animator and director’s films — but they’re incredible and I must have more. I’ve been a fan of Ray Harryhausen’s work since childhood, and Karel Zeman’s adventures hit the same spot, though the films are far more consistent in tone, given his broader control. His method of mixing animation and live-action is more pragmatic than Harryhausen’s too, with a mix of media that avoids the need for “realism.” Journey to the Beginning of Time (1955) is a sweet child-led dinosaur adventure that my 3- and 6-year-old sons love. Invention for Destruction (1958) is an amalgam of Jules Verne tales that also recalls the best of special effects pioneer Georges Méliès. The Fabulous Baron Munchausen (1961) is a wild, hallucinogenic ride with elaborate sets mimicking Gustave Doré’s etchings and was the primary influence on Terry Gilliam’s own Munchausen film. A Jester’s Tale (1964) is a black comedy set in the 1600s, which comes across like a combination of Milos Forman and Monty Python.

November (Rainer Sarnet, 2017)

Possibly the only, and therefore the best, Estonian film I’ve ever seen, but also one of the weirdest from any country. Set in a pagan village, the loose story revolves around “kratts,” bizarre creatures made of wood and farmyard tools and who-knows-what, whose purpose is to guard villagers’ souls — though in fact this requires those same villagers to have bartered their souls away in the first place. I mean, that’s sort of what it’s about. I think. There are werewolves and ghosts and the devil and the shadow of the Black Death, and the tone is a combination of the bleakest of Grimms’ tales with the magical realism of Gabriel García Márquez. The kratts’s jerky movements evoke the most out-there extremes of Czech animator Jan Švankmajer. And the cinematography! Sharply monochrome, with every detail utterly clean and clear, whilst at the same time leaving everything opaque and upsetting in its ambiguity.

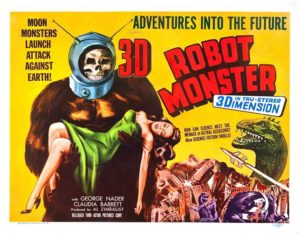

Robot Monster (Phil Tucker, 1953)

I love bad films, from the glorious nonsense of Dünyayı Kurtaran Adam (known as Turkish Star Wars) to the staggering stupidity of Birdemic: Shock and Terror to the po-faced amateurishness of The Room. But the real prize, as far as I’m concerned, is a film that is simultaneously awful and genuinely wonderful. Parts of Troll 2 fall into that category, but the ultimate example is Robot Monster. I mean, okay, the monster itself — some poor guy lumbering around in a gorilla suit and sporting a diving helmet, and about as un-robotic a creature as you could possibly imagine — is absurd, as is its name, “Ro-Man” (I mean, really?). But there’s a creeping uneasiness to the post-apocalyptic plot and the nightmare framing narrative that lingers long after the belly laughs have faded.

I love bad films, from the glorious nonsense of Dünyayı Kurtaran Adam (known as Turkish Star Wars) to the staggering stupidity of Birdemic: Shock and Terror to the po-faced amateurishness of The Room. But the real prize, as far as I’m concerned, is a film that is simultaneously awful and genuinely wonderful. Parts of Troll 2 fall into that category, but the ultimate example is Robot Monster. I mean, okay, the monster itself — some poor guy lumbering around in a gorilla suit and sporting a diving helmet, and about as un-robotic a creature as you could possibly imagine — is absurd, as is its name, “Ro-Man” (I mean, really?). But there’s a creeping uneasiness to the post-apocalyptic plot and the nightmare framing narrative that lingers long after the belly laughs have faded.

Four Sided Triangle (Terence Fisher, 1953)

This early gem from Hammer Films, taken alongside The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and its sequels, gives a tantalizing suggestion of the kind of SF output that the company might have continued to produce if The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) hadn’t established it as the home of British Gothic horror. Four Sided Triangle concerns two male friends who create a “Reproducer” (hmm) which allows cloning of any object, but their mutual attraction to their childhood friend, Lena, prompts one of the inventors to clone her rather than, for example, an attempt to solve world hunger or even just make himself rich. The film plays the idea totally straight, but any modern viewer can’t help but become fascinated and then appalled by the ethical dilemma and the issue of Lena’s consent, or rather the lack of it. Consequently, I consider it an inadvertent horror film, and one of the most unsettling I’ve seen in a long time. I’m grateful I saw it after writing my own SF clone novel, Snakeskins, though equally the film does make me want to write a sequel addressing all of its queasy implications.

This early gem from Hammer Films, taken alongside The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and its sequels, gives a tantalizing suggestion of the kind of SF output that the company might have continued to produce if The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) hadn’t established it as the home of British Gothic horror. Four Sided Triangle concerns two male friends who create a “Reproducer” (hmm) which allows cloning of any object, but their mutual attraction to their childhood friend, Lena, prompts one of the inventors to clone her rather than, for example, an attempt to solve world hunger or even just make himself rich. The film plays the idea totally straight, but any modern viewer can’t help but become fascinated and then appalled by the ethical dilemma and the issue of Lena’s consent, or rather the lack of it. Consequently, I consider it an inadvertent horror film, and one of the most unsettling I’ve seen in a long time. I’m grateful I saw it after writing my own SF clone novel, Snakeskins, though equally the film does make me want to write a sequel addressing all of its queasy implications.

Vampir Cuadecuc (Pere Portabella, 1970)

Ostensibly a behind-the-scenes documentary about the filming of Jess Franco’s Count Dracula, this fairly short, almost silent film is actually one of the strangest and most compelling bits of cinema I’ve ever seen. The high-contrast monochrome film stock abstracts everything, and the combination of familiar scenes from Dracula with the mundane elements of film-making (smoke machines, shots from the wrong side of wooden sets, actors pulling faces between takes, Christopher Lee as Dracula clambering into his coffin to be covered in fake spiderwebs, or fiddling with a gruesome contact lens) produces the most peculiar effect, leaving you with the strange feeling that perhaps the entire world is somewhat fake and unreliable.

The Films of Josef von Sternberg featuring Marlene Dietrich

I saw and loved The Blue Angel (1930) years ago, but only came to the American sequence of films made with the pairing of actress Marlene Dietrich and director Josef von Sternberg recently, when Indicator released its terrific box set in the UK. The six films that they made at Paramount after leaving Germany are oddly comforting (when watched as a sequence, at least: what will Marlene get up to this time around?) and astounding (sexual explicitness, hazy morals, gloriously beautiful). When watched nowadays, the limitations that would later be imposed by the “moral guidelines” of the Hays Production Code seem all the more frustrating, and so is the sense that it would take another 70 years or so for more films to be greenlit with female leads as effortlessly powerful as Dietrich.

I saw and loved The Blue Angel (1930) years ago, but only came to the American sequence of films made with the pairing of actress Marlene Dietrich and director Josef von Sternberg recently, when Indicator released its terrific box set in the UK. The six films that they made at Paramount after leaving Germany are oddly comforting (when watched as a sequence, at least: what will Marlene get up to this time around?) and astounding (sexual explicitness, hazy morals, gloriously beautiful). When watched nowadays, the limitations that would later be imposed by the “moral guidelines” of the Hays Production Code seem all the more frustrating, and so is the sense that it would take another 70 years or so for more films to be greenlit with female leads as effortlessly powerful as Dietrich.

Tim Major is a writer and editor from York in the UK. His love of speculative fiction is the product of a childhood diet of classic Doctor Who episodes and an early encounter with Triffids. His most recent books include SF novel Snakeskins, short story collection And the House Lights Dim and a non-fiction book about the 1915 silent crime film, Les Vampires, which was shortlisted for a British Fantasy Award. His short stories have appeared in Interzone, Not One of Us and numerous anthologies, including Best of British Science Fiction and Best Horror of the Year. Find out more at www.cosycatastrophes.com or on Twitter @onasteamer.

Tim Major is a writer and editor from York in the UK. His love of speculative fiction is the product of a childhood diet of classic Doctor Who episodes and an early encounter with Triffids. His most recent books include SF novel Snakeskins, short story collection And the House Lights Dim and a non-fiction book about the 1915 silent crime film, Les Vampires, which was shortlisted for a British Fantasy Award. His short stories have appeared in Interzone, Not One of Us and numerous anthologies, including Best of British Science Fiction and Best Horror of the Year. Find out more at www.cosycatastrophes.com or on Twitter @onasteamer.

Author Photo by Rose Parkin

Would you like to write about YOUR favorite things for Speculative Chic? Check out our guidelines and fill out the form here.

Thanks so much for joining us!!! That November film looks fascinating!!!