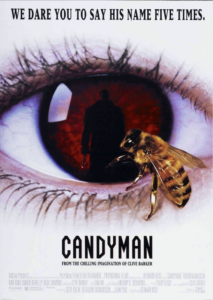

The High Unholy Days of October continue with The Kasturi/Files at Speculative Chic, now with a spanking new movie for Day 9! Plus, of course, cocktail and book pairings. Today we’re covering the ’90s horror classic, Candyman.

Gemma Files: It makes total sense to me that Jordan Peele (Get Out, Us) is spearheading the less-a-reboot-than-a-sequel of Bernard Rose’s 1992 “supernatural slasher” Candyman that’s currently scheduled for a 2020 release, since the original Candyman — made for nine million, reaping a $25 million plus domestic gross — was the first film I’d ever seen to address the racial politics of America head-on, even in a highly metaphorical way. What’s depressing, in fact, is exactly how woke it still remains, long after both the destruction of Cabrini-Green (the notoriously dangerous Chicago housing project in which much of the original movie takes place, and part of it was shot) and two terms of a black president. At the time, I thought the cold eye it cast on an America where The Cosby Show produced such an exportable vision of black-middle-class existence that it had become segregated South Africa’s favorite sitcom, yet inner city neighborhoods still struggled against the same crack cocaine epidemic which Mario van Peebles had chronicled in New Jack City just the year before, had a lot to do with the fact that it was directed by an Englishman, the same way RoboCop‘s excoriating 1987 vision of a corporate-owned near future Detroit was directed by a Dutch man (Paul Verhoeven). It seemed fresh as hell in its day, at least to this white-as-a-sheet Canadian.

Gemma Files: It makes total sense to me that Jordan Peele (Get Out, Us) is spearheading the less-a-reboot-than-a-sequel of Bernard Rose’s 1992 “supernatural slasher” Candyman that’s currently scheduled for a 2020 release, since the original Candyman — made for nine million, reaping a $25 million plus domestic gross — was the first film I’d ever seen to address the racial politics of America head-on, even in a highly metaphorical way. What’s depressing, in fact, is exactly how woke it still remains, long after both the destruction of Cabrini-Green (the notoriously dangerous Chicago housing project in which much of the original movie takes place, and part of it was shot) and two terms of a black president. At the time, I thought the cold eye it cast on an America where The Cosby Show produced such an exportable vision of black-middle-class existence that it had become segregated South Africa’s favorite sitcom, yet inner city neighborhoods still struggled against the same crack cocaine epidemic which Mario van Peebles had chronicled in New Jack City just the year before, had a lot to do with the fact that it was directed by an Englishman, the same way RoboCop‘s excoriating 1987 vision of a corporate-owned near future Detroit was directed by a Dutch man (Paul Verhoeven). It seemed fresh as hell in its day, at least to this white-as-a-sheet Canadian.

Which isn’t, of course, to imply that things haven’t gotten at least marginally more woke since then, at least in terms of running stuff through a diversity consultant every now and then — as Tananarive Due points out, the main plot of the 1992 Candyman still has a black man romantically chasing after a white woman who also provides the audience’s entry-point and POV character, while her black sidekick (Kasi Lemmons, director and co-director of this year’s Harriet) ends up spitted on a hook. Today, it’s entirely possible that even without Peele to champion it, the new Candyman installment might still have automatically picked up both a black director, a black main character, and a mostly black cast: i.e. been driven by action from within the legacy of the slavery-infected neighborhood in question, as well as from outside it — sort of like 2018’s The First Purge, or (as I like to call it) The Purge: No White Saviors Edition, Which Is Why It’s Told In Flashback, Because Hillary Didn’t Actually End Up Getting Elected. But there’s a reason The First Purge takes place on Staten Island, to my mind: America still labors under the delusion that racism isn’t really everybody’s problem, when it so obviously, obviously is. Just like everywhere else in the fucking world.

Sandra Kasturi: Tananarive Due is absolutely right — but I also think that by having a white female POV character, Rose makes the audience complicit in the very racism he’s pointing out. And I wonder if that isn’t intentional? Hm.

Gemma: Hm. At any rate: Candyman.

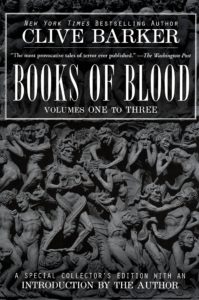

Bernard Rose came to the film off of Paperhouse (1988, another sadly undersung movie, though marketed more as dark fantasy), and his screenplay was based on “The Forbidden,” a Clive Barker short story first published as part of his Books of Blood, which posits a sweets-loving monster cobbled together from a thousand urban legends who spawns fear and invites worship amongst inhabitants of the same public housing units that eventually gave rise to Attack the Block. In adapting the tale, Rose did two incredibly smart things. First off, he shifted the action from London’s slums to Cabrini-Green, the same place Frank Miller cited as world-saving Afro-American child soldier Martha Washington’s birthplace in his 1990 Give Me Liberty graphic novel, twisting the demand that Candyman be set in America to produce a layer of racial examination which might otherwise have gone uncharted. And secondly . . . he hired Tony Todd to play Candyman.

Bernard Rose came to the film off of Paperhouse (1988, another sadly undersung movie, though marketed more as dark fantasy), and his screenplay was based on “The Forbidden,” a Clive Barker short story first published as part of his Books of Blood, which posits a sweets-loving monster cobbled together from a thousand urban legends who spawns fear and invites worship amongst inhabitants of the same public housing units that eventually gave rise to Attack the Block. In adapting the tale, Rose did two incredibly smart things. First off, he shifted the action from London’s slums to Cabrini-Green, the same place Frank Miller cited as world-saving Afro-American child soldier Martha Washington’s birthplace in his 1990 Give Me Liberty graphic novel, twisting the demand that Candyman be set in America to produce a layer of racial examination which might otherwise have gone uncharted. And secondly . . . he hired Tony Todd to play Candyman.

Sandra: I had read all of Barker’s Books of Blood, so was interested to see what the film adaptation would look like. I didn’t mind, for once, the change of locale from England to America. (Which so often gets handled horribly poorly, and smacks of a kind of American imperialism in its own way.) As you say, though, it offers an opportunity to look at racial as well as class issues in America, and, yeah, just as relevant today as it ever was in the ’90s. Which begs the question: have we learned nothing? Maybe not. Candyman is there to tell us we need to step it the fuck up; we’re just not hearing him. Maybe he can use that hook to clean out our ears.

Ah, Tony Todd. He’s so electric, so compelling! So enormous! He seems perfectly suited and destined to play a role that casts him as a vengeful, powerful, mythological character. He eats up the screen every time he appears.

And I love the trope of saying Candyman’s name into the mirror to conjure him. It suggests children’s games, and the creepiness inherent therein. Conjuring is about repetition after all. And what you say often enough becomes the de facto truth.

Gemma: The basic plot goes like this: graduate student Helen Lyle (Virginia Madsen at her peak creamiest, casually zaftig-glamorous, slightly uneven eyes gleaming with an intelligence that’s offputtingly close to zealotry) is interviewing University of Chicago freshmen in order to track urban legends for a potential thesis project when she and her study partner Bernadette (Lemmons) trip across something they think no one’s ever heard about before — a variation on the classic 1950s-era Man With A Hook tale involving a phantom who supposedly haunts current-day Cabrini-Green, where residents blame him for a string of very modern murders. This, in turn, leads them to the historical Candyman, his real name lost to time, artistically inclined son of a former slave who became rich after the Civil War by inventing “a device for the manufacture of shoe-hooks.” Raised to consider himself beyond race by virtue of his wealth and talent, Candyman fell in love with a woman he’d been hired to paint, the beautiful — white — daughter of a wealthy Chicagoan, and was lynched for his uppitiness in legendarily yet sadly typical fashion on the same ground where Cabrini-Green was eventually built. Now he preys on its inhabitants rather than the forces which keep them there, as if subtextually still pissed off to be relegated to kinship with people he considers beneath him due to a simple accidental excess of melanin in his ghostly skin.

Gemma: The basic plot goes like this: graduate student Helen Lyle (Virginia Madsen at her peak creamiest, casually zaftig-glamorous, slightly uneven eyes gleaming with an intelligence that’s offputtingly close to zealotry) is interviewing University of Chicago freshmen in order to track urban legends for a potential thesis project when she and her study partner Bernadette (Lemmons) trip across something they think no one’s ever heard about before — a variation on the classic 1950s-era Man With A Hook tale involving a phantom who supposedly haunts current-day Cabrini-Green, where residents blame him for a string of very modern murders. This, in turn, leads them to the historical Candyman, his real name lost to time, artistically inclined son of a former slave who became rich after the Civil War by inventing “a device for the manufacture of shoe-hooks.” Raised to consider himself beyond race by virtue of his wealth and talent, Candyman fell in love with a woman he’d been hired to paint, the beautiful — white — daughter of a wealthy Chicagoan, and was lynched for his uppitiness in legendarily yet sadly typical fashion on the same ground where Cabrini-Green was eventually built. Now he preys on its inhabitants rather than the forces which keep them there, as if subtextually still pissed off to be relegated to kinship with people he considers beneath him due to a simple accidental excess of melanin in his ghostly skin.

Loomingly large and deep-voiced enough to make tabletops rattle, Todd cuts an aristocratic figure in his 1880s-era astrakhan coat, treating the rusty hook that replaces one of his hands like a rakish affectation; he doesn’t haul his exposed ribcage full of bees and honeycomb out on the first date, saving it for truly special ladies like our heroine, too fiercely fearless in her quest for knowledge to know not to crawl through the backs of the same mirrors that tales say you summon Candyman with, by saying his name five times while looking into. There’s some intimation that Helen even may share genes with the woman who brought Candyman to his current pass, the lover who didn’t care about anything but his genius or her pregnancy . . . but really, it doesn’t matter. As Philip Glass’s brilliant, looping score rises up, an organ constructed from human voices, we begin to feel that he’s been stuck killing people he doesn’t identify with enough to give a damn about, for so long — he sees even the prospect of Helen possibly being the one to finally defeat him as a win.

Sandra: What Candyman does so well is to subvert the idea of how we “win” against evil, or even how we decide what “evil” is. Is Candyman violent and vengeful? Absolutely yes. But maybe deservedly so, or rather, understandably so. He’s there to mete out justice of a sort, perhaps unfairly. You can argue that he is cruel, but what god isn’t, especially faced with non-believers?

Helen does get to win in the end — she is given immortality and becomes a kind of vengeful Fury herself, giving her cheating husband his comeuppance, and achieving apotheosis through art/graffiti — and true love’s kiss? True love of a terrible sort. But I was never able to shake the feeling that there’s something in Helen that draws Candyman to her — not just the obvious idea that she is either the reincarnation of his lost love, or perhaps her descendant. But that the seed of destruction and vengeance has been dormant in Helen all along; she is in fact the perfect mate? match? acolyte? for Candyman. His partner in crime, or perhaps the heir to his bloody empire.

There’s a scene near the start of the film that I keep coming back to. Helen goes to see her husband, Trevor Lyle (played by the criminally underrated Xander Berkeley) at one of his university lectures. The student/TA he’s been sleeping with is there. The body language is so great. . . . All three of them aren’t saying what’s really going on: that Trevor is banging the student, that Helen (also a grad student! therefore history repeating?) is aware of it; Trevor knows his wife knows, so does the student . . . It’s an uncomfortable scene. The look Virginia Madsen gives Xander Berkeley is worthy of an Oscar, conveying multitudes in just a few seconds. That “I know you’re a lying cheater but I’m not going to make a scene right now in front of this Twinkie, but don’t think for one second I don’t know.” There’s a world-weariness to it, and an implication that this isn’t the first time it has happened. Helen, like so many women of her generation, is married to a man who isn’t worthy of her. But in another instance of history repeating, she finds her… real love? Sadistic soulmate? Fellow standard-bearer for Absolute Justice? — in Tony Todd’s Candyman. Who both destroys and saves her, and… elevates her to the truest version of herself, perhaps, terrible as that might be.

Ultimately Candyman is about things hidden, things forbidden. Important issues like America’s secret (non-white) history and shameful legacies, coupled with white America’s collective decision to actively ignore terrible racial inequalities and to hide its own prejudice from itself while smugly patting itself on the back for being the “leader of the free world,” an expression I really don’t need to hear again in my lifetime. And the (comparatively) unimportant, but still thematically on point, matters of spouses keeping secrets and having hidden lives.

That graffiti head with the open mouth ready to swallow you whole. I can’t think about it before bedtime. That doorway to terrible self-knowledge.

I just want to add that it’s great to see the amazing Xander Berkeley, who delivers in pretty much every movie he’s in, in a lead role, and if you haven’t seen The Booth at the End, I highly, highly recommend it as a compelling take on the Faustian myth, which sadly only ran two short seasons. Looks like it’s available on Amazon Prime, and you can still occasionally find DVDs of it for those who like that sort of thing. As I do.

Gemma: One way or the other, this is a film that I will never tire of… a difficult, interweaving narrative full of passion and pain, which takes its structure from a nested series of stories inside of stories: Rumor, myth, innuendo, facts reshaped into fiction and back again. Just as Candyman inverts his own narrative, becoming all-powerful through his own victimization, Helen “falls” from privilege simply by learning that he exists, hitting every possible marker along the way, going over the space of days from a respected, happily married white academic to a homeless, demented murder suspect who keeps on screaming about that scary black man who wants to kill her. As he asks her, ruefully: “Why do you want to live? If you would learn just a little from me, you would not beg to live. I am rumor. It is a blessed condition, believe me. To be whispered about at street corners. To live in other people’s dreams, but not to have to be. Do you understand?”

Cocktail: Candyman Cognac Cocktail

Sandra: Ask and ye shall receive! This one is from Kegworks and might be too sweet for some, though the cognac might mitigate that.

Sandra: Ask and ye shall receive! This one is from Kegworks and might be too sweet for some, though the cognac might mitigate that.

- 1 ½ oz Cognac.

- ¾ oz Sweet vermouth.

- ¾ oz Amaro.

- ¼ oz Creme de cacao.

- Dash of chocolate bitters.

- Maraschino cocktail cherries (for garnish)

Put some ice in a pre-chilled glass, then add all the ingredients, except the cherries. Stir for 30 to 45 seconds to chill. You can drink as is, or strain into a specialty glass like a skull one, or maybe one that’s the gaping graffiti mouth from Cabrini-Green. Top with a cherry. Personally, I think Maraschino cherries are disgusting, but go ahead and plonk them in there if you must.

Book Recommendations

Sandra: I’m going to let Gemma take this one, since she and I are both on board the same book express for this round!

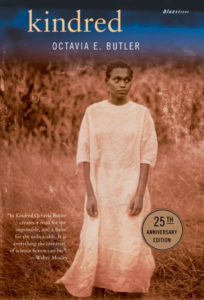

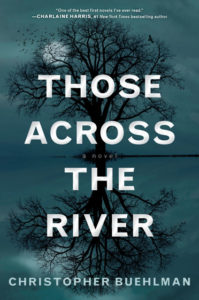

Gemma: My book recs are Octavia E. Butler’s Kindred and Those Across the River by Christopher Buehlman.

Butler’s book introduces us to Dana, a contemporary black author married to a white man, who falls through time while celebrating her twenty-sixth birthday and ends up accidentally saving a red-headed white boy from drowning, only to discover he will grow up to be the man who owned her direct ancestors. To Rufus, Dana becomes a figure of supernatural power who reappears whenever he’s in danger — but because she’s also a “white-talking impudent [n-word],” the only way he can deal with her apparent power over him is to exert his “natural” power over her as a slave-owner in a slavery-based society, to increasingly awful effects. On the one hand, Dana worries that if she doesn’t keep on saving him, he’ll never father the children she’s descended from . . . but she can’t save him from becoming the monster slavery allows him to be. It’s an incredibly painful read, but curt, true and gorgeous all the same.

Buehlman’s book, on the other hand, is ostensibly about werewolves who occupy a former Louisiana slave plantation and are tolerated/cleaned up after by the local villagers, mainly because they’re far too strong and vicious not to be. But here, too, the horrid legacy of slavery is what powers the werewolves’ eternal hatred for all white people . . . especially our protagonist, himself the great-great-grandson of the man who once hunted them like foxes every full moon.

Sandra Kasturi is the publisher of ChiZine Publications, winner of the World Fantasy, British Fantasy, and HWA Specialty Press Awards. She is the co-founder of the Toronto SpecFic Colloquium and the Executive Director of the Chiaroscuro Reading Series, and a frequent guest speaker, workshop leader, and panelist at genre conventions. Sandra is also an award-winning poet and writer, with work appearing in various venues, including Amazing Stories, Black Feathers: Dark Avian Tales, Prairie Fire, several Tesseracts anthologies, Evolve, Chilling Tales, ARC Magazine, Taddle Creek, Abyss & Apex, Stamps, Vamps & Tramps, and 80! Memories & Reflections on Ursula K. Le Guin. She recently won the Sunburst Award for her short story, “The Beautiful Gears of Dying,” in the anthology The Sum of Us. Her two poetry collections are: The Animal Bridegroom (with an introduction by Neil Gaiman) and Come Late to the Love of Birds. Sandra is currently working on another poetry collection, Snake Handling for Beginners, a story collection, Mrs. Kong & Other Monsters, and a novel, Wrongness: A False Memoir. She is fond of red lipstick, gin & tonics, and Idris Elba.

Sandra Kasturi is the publisher of ChiZine Publications, winner of the World Fantasy, British Fantasy, and HWA Specialty Press Awards. She is the co-founder of the Toronto SpecFic Colloquium and the Executive Director of the Chiaroscuro Reading Series, and a frequent guest speaker, workshop leader, and panelist at genre conventions. Sandra is also an award-winning poet and writer, with work appearing in various venues, including Amazing Stories, Black Feathers: Dark Avian Tales, Prairie Fire, several Tesseracts anthologies, Evolve, Chilling Tales, ARC Magazine, Taddle Creek, Abyss & Apex, Stamps, Vamps & Tramps, and 80! Memories & Reflections on Ursula K. Le Guin. She recently won the Sunburst Award for her short story, “The Beautiful Gears of Dying,” in the anthology The Sum of Us. Her two poetry collections are: The Animal Bridegroom (with an introduction by Neil Gaiman) and Come Late to the Love of Birds. Sandra is currently working on another poetry collection, Snake Handling for Beginners, a story collection, Mrs. Kong & Other Monsters, and a novel, Wrongness: A False Memoir. She is fond of red lipstick, gin & tonics, and Idris Elba.

Formerly a film critic, journalist, screenwriter and teacher, Gemma Files has been an award-winning horror author since 1999. She has published two collections of short work, two chap-books of speculative poetry, a Weird Western trilogy, a story-cycle and a stand-alone novel (Experimental Film, which won the 2016 Shirley Jackson Award for Best Novel and the 2016 Sunburst award for Best Adult Novel). Most are available from ChiZine Publications. She has two new story collections from Trepidatio (Spectral Evidence and Drawn Up From Deep Places), one upcoming from Cemetery Dance (Dark Is Better), and a new poetry collection from Aqueduct Press (Invocabulary).

Formerly a film critic, journalist, screenwriter and teacher, Gemma Files has been an award-winning horror author since 1999. She has published two collections of short work, two chap-books of speculative poetry, a Weird Western trilogy, a story-cycle and a stand-alone novel (Experimental Film, which won the 2016 Shirley Jackson Award for Best Novel and the 2016 Sunburst award for Best Adult Novel). Most are available from ChiZine Publications. She has two new story collections from Trepidatio (Spectral Evidence and Drawn Up From Deep Places), one upcoming from Cemetery Dance (Dark Is Better), and a new poetry collection from Aqueduct Press (Invocabulary).

I have never seen this, but after reading your discussion, I really, really want to. Also, KINDRED, like all of Octavia Butler’s work, is AMAZING, and you’ve sold me on THOSE ACROSS THE RIVER.

I’ve never seen this movie but have always been curious. I’ve also read both books and while the finish to Kindred drove me bonkers, Those Across the River was pretty solid and very different.

Wait no – not Kindred. I thinking of another book by Octavia Butler. Haven’t read Kindred, but have heard nothing but good things since forever!

I love all of Octavia Butler, all of the time! Particularly loved Parable of the Sower.