August has many meaningful historical anniversaries:

- Martin Luther King, Jr’s “I Have a Dream” speech at the Freedom March

- President Nixon’s resignation

- the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- union strikes result in adoption of workday limits

- the Watts riots in L.A.

- the Social Security Act signed into effect

- Hurricane Katrina devastates the Gulf Coast

- the Salem “witch” trials

- the ratification of the 19th Amendment

–and Anne Frank’s last diary entry, three days before she was captured by the Gestapo and taken to Auschwitz, then transferred to Bergen-Belsen, where she and her sister died from typhus, six months after their capture.

It isn’t easy to talk about heavy subjects such as internment. Science fiction and fantasy has not, as a rule, shied away from difficult subject matter on any moral or ethical level—the first interracial kiss, the ethics of cloning, colonizing worlds, is artificial intelligence life—just a few of the themes to be found in any ten books brought home from the library or bookstore. In fact, power imbalances are the core of many a story conflict, are they not? This post is rather sober. But I believe it’s necessary to keep these things at the forefront of our minds so that we will recognize them when history inevitably repeats itself. When I heard people discussing the policy of separating minors from their parents at the border–people who came to seek asylum (be clear, it should not be a crime to seek asylum; start here for laws, codes and explanations), one of the mantras I heard was “This is not the United States I know. We don’t do this.”

But we do. We have. We made Native peoples leave their homelands and march cross-country to live on inhospitable terrain because we wanted their land; we forced adults and children alike to dress in a Western manner, adopt religion and the English language; we took children from their parents and sent them to schools to obliterate their sense of self and culture. Based on nothing but rumors and fear, one of the most well-regarded presidents in the history of this country signed executive orders to remove Japanese citizens to internment camps. So it has happened. Let’s acknowledge that. And then let’s make sure it doesn’t continue.

Reading fiction helps create empathy, so I’ve chosen a few stories from print, film, and television that illustrate the dangers of dehumanizing people.

The Immortals, Tracy Hickman (1996). This is the most resonant work I’ve read with this theme. Hickman is famous for writing Dragonlance novels with Margaret Weis and fantasy novels with his wife Laura, but he has a few solo works all his own, and The Immortals is one of his only works that is not part and parcel of a franchise. Hickman has also proclaimed it as his personal favorite. It has been many years since I cracked open this book, but the lesson stayed with me—it packs quite a punch. A cure for AIDS has morphed into the even deadlier V-CIDS, and the government orders anyone with the disease—and anyone in contact with them–to be quarantined in camps located in the Southwest. Young gay man Jason Barris is on the run from forced government encampment, trying to reach his media CEO father, Michael—even though Michael’s involvement with the media helped create the furor and paranoia leading to the camps. When Jason is caught and taken to Newhouse Center—rights as a U.S. citizen suspended, of course, since he is now termed “predeceased”—Michael gets himself incarcerated to find his son, and discovers the real fate intended for them. The allegory works on several levels, especially if you know the history of AIDS as a “gay disease;” if you don’t, this book is a good starting point. Some of it may feel dated; in the 1990s this counted as a coming-out story. Its plot points, however, are chillingly appropriate for today.

The Immortals, Tracy Hickman (1996). This is the most resonant work I’ve read with this theme. Hickman is famous for writing Dragonlance novels with Margaret Weis and fantasy novels with his wife Laura, but he has a few solo works all his own, and The Immortals is one of his only works that is not part and parcel of a franchise. Hickman has also proclaimed it as his personal favorite. It has been many years since I cracked open this book, but the lesson stayed with me—it packs quite a punch. A cure for AIDS has morphed into the even deadlier V-CIDS, and the government orders anyone with the disease—and anyone in contact with them–to be quarantined in camps located in the Southwest. Young gay man Jason Barris is on the run from forced government encampment, trying to reach his media CEO father, Michael—even though Michael’s involvement with the media helped create the furor and paranoia leading to the camps. When Jason is caught and taken to Newhouse Center—rights as a U.S. citizen suspended, of course, since he is now termed “predeceased”—Michael gets himself incarcerated to find his son, and discovers the real fate intended for them. The allegory works on several levels, especially if you know the history of AIDS as a “gay disease;” if you don’t, this book is a good starting point. Some of it may feel dated; in the 1990s this counted as a coming-out story. Its plot points, however, are chillingly appropriate for today.

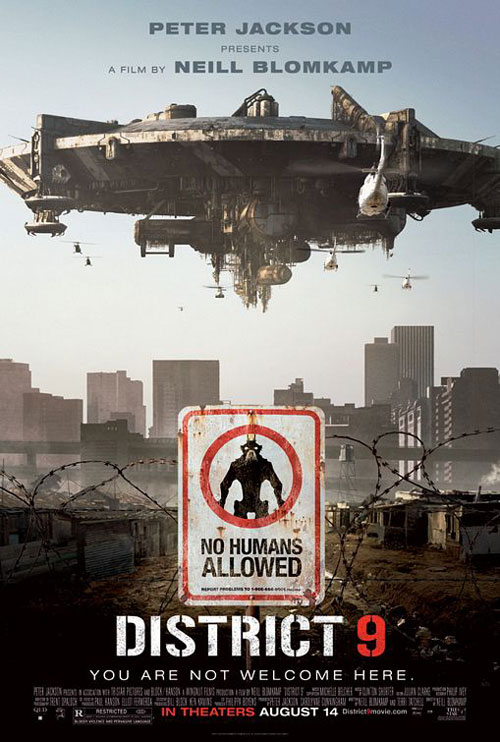

District 9 (2009). South African director Neill Blomkamp hones in on an allegory about apartheid in this stunning, action-packed, robot/alien mashup, alternative-history science fiction movie about first contact—except that we imprisoned the aliens after they arrived in 1982. While overseeing relocation of the aliens to yet another camp (to reappropriate the land), government minion Wikus van de Merwe accidentally comes into contact with alien body fluid, which causes him to mutate on a cellular level into an alien. Desperate to remain human, Wikus runs a job for one alien who promises to change him back if Wikus delivers a power source for the ship he is secretly building to leave Earth. The movie received criticism for white savior syndrome as well as its treatment of Nigerian characters, but the plot twist allows a brutally honest, empathetic look at the problem of internment. That same twist may negate some of the white savior criticism as well, given the very end of the film; but nonetheless these are good things to be aware of when watching District 9.

District 9 (2009). South African director Neill Blomkamp hones in on an allegory about apartheid in this stunning, action-packed, robot/alien mashup, alternative-history science fiction movie about first contact—except that we imprisoned the aliens after they arrived in 1982. While overseeing relocation of the aliens to yet another camp (to reappropriate the land), government minion Wikus van de Merwe accidentally comes into contact with alien body fluid, which causes him to mutate on a cellular level into an alien. Desperate to remain human, Wikus runs a job for one alien who promises to change him back if Wikus delivers a power source for the ship he is secretly building to leave Earth. The movie received criticism for white savior syndrome as well as its treatment of Nigerian characters, but the plot twist allows a brutally honest, empathetic look at the problem of internment. That same twist may negate some of the white savior criticism as well, given the very end of the film; but nonetheless these are good things to be aware of when watching District 9.

Winter Tide (2017), Ruthanna Emrys (Innsmouth Legacy series). This series is preceded by a 2014 short story, “The Litany of Earth” written for TOR, that introduced Aphra Marsh, bookstore assistant and internment camp survivor, and which continues in Deep Roots (2018). Emrys presents an alternate reality that dovetails, then resonates all too well with our own. In 1928, acting on rumors, the U.S. Government rounded up all worshippers of Cthulhu and placed them in internment camps out west. Twenty years later, Aphra and her brother Caleb are the only survivors; everyone else has succumbed to time or, worse, subjected to state-sanctioned torture. I’ve barely read any Lovecraft (my spellchecker corrected Cthulhu for me)—but a passing familiarity with Lovecraftian mythology is all one needs to appreciate the nuances of Emrys’s series. Aphra and Caleb grew up in the internment camp, eventually finding a new family when the U.S. encamps Japanese citizens during WWII. Four years after the end of that war, Aphra is approached by government agent Ron Spector, who believes certain items from Aphra’s religion have fallen into the wrong hands. Aphra assembles her family and friends—her boss, Charlie, the bookstore owner, to whom she is teaching magic; her distant brother Caleb, who bears the scars of internment; and Neko, the daughter of the Japanese woman whose family has bonded with Aphra. They return to Innsmouth where Aphra is forced to confront the horrors of her past. Emrys’s work is lyrical and humanizing, and the themes of loyalty and betrayal are strong throughout. The second book, Deep Roots, just came out, and I haven’t yet read it because I’m still mulling over Winter Tide, which is one of the best debut novels I’ve ever read.

Winter Tide (2017), Ruthanna Emrys (Innsmouth Legacy series). This series is preceded by a 2014 short story, “The Litany of Earth” written for TOR, that introduced Aphra Marsh, bookstore assistant and internment camp survivor, and which continues in Deep Roots (2018). Emrys presents an alternate reality that dovetails, then resonates all too well with our own. In 1928, acting on rumors, the U.S. Government rounded up all worshippers of Cthulhu and placed them in internment camps out west. Twenty years later, Aphra and her brother Caleb are the only survivors; everyone else has succumbed to time or, worse, subjected to state-sanctioned torture. I’ve barely read any Lovecraft (my spellchecker corrected Cthulhu for me)—but a passing familiarity with Lovecraftian mythology is all one needs to appreciate the nuances of Emrys’s series. Aphra and Caleb grew up in the internment camp, eventually finding a new family when the U.S. encamps Japanese citizens during WWII. Four years after the end of that war, Aphra is approached by government agent Ron Spector, who believes certain items from Aphra’s religion have fallen into the wrong hands. Aphra assembles her family and friends—her boss, Charlie, the bookstore owner, to whom she is teaching magic; her distant brother Caleb, who bears the scars of internment; and Neko, the daughter of the Japanese woman whose family has bonded with Aphra. They return to Innsmouth where Aphra is forced to confront the horrors of her past. Emrys’s work is lyrical and humanizing, and the themes of loyalty and betrayal are strong throughout. The second book, Deep Roots, just came out, and I haven’t yet read it because I’m still mulling over Winter Tide, which is one of the best debut novels I’ve ever read.

V: the Miniseries (1983); V: The Final Battle (1984); and V: The Series (1984-85; reboot, 2009-2011). We’ve talked about V before (go here and here). The brainchild of producer Kenneth Johnson (who also gave us The Bionic Woman, The Incredible Hulk, and Alien Nation), V was a direct allegory to Nazi Germany (“First they came for the…”) and was inspired by Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here (I’ll let you look that up). I don’t think anyone is going to be surprised by plot revelations, but just in case, the major spoilers are down below in the discussion of The Fire Sermon. Where Hickman’s The Immortals covers the gritty, terrible realities of internment, V was concerned with illuminating the secretive political alliances and machinations that served Hitler’s regime so well in their horrific endeavors to wipe out a people, and it was concerned with rebellion. Everyone was represented: the oppressors; those courting their power; the victims; survivors of the Holocaust who knew what was going on; the scared but determined scientists, journalists, mercs and ne’er-do-wells who formed the core of the Resistance; and the Fifth column–aliens turned spies because they didn’t believe in the mission. Although the special effects may seem cheesy at this point, V is well worth watching for many reasons.

V: the Miniseries (1983); V: The Final Battle (1984); and V: The Series (1984-85; reboot, 2009-2011). We’ve talked about V before (go here and here). The brainchild of producer Kenneth Johnson (who also gave us The Bionic Woman, The Incredible Hulk, and Alien Nation), V was a direct allegory to Nazi Germany (“First they came for the…”) and was inspired by Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here (I’ll let you look that up). I don’t think anyone is going to be surprised by plot revelations, but just in case, the major spoilers are down below in the discussion of The Fire Sermon. Where Hickman’s The Immortals covers the gritty, terrible realities of internment, V was concerned with illuminating the secretive political alliances and machinations that served Hitler’s regime so well in their horrific endeavors to wipe out a people, and it was concerned with rebellion. Everyone was represented: the oppressors; those courting their power; the victims; survivors of the Holocaust who knew what was going on; the scared but determined scientists, journalists, mercs and ne’er-do-wells who formed the core of the Resistance; and the Fifth column–aliens turned spies because they didn’t believe in the mission. Although the special effects may seem cheesy at this point, V is well worth watching for many reasons.

The Fire Sermon (2014), Francesca Haig (followed by The Map of Bones (2016) and The Forever Ship (2017). I liked The Fire Sermon because it was so different than some other dystopic science fiction fantasies I’ve read; for one thing, it does not drag in the middle, which I think is a weakness for many authors. (To be fair, middles are difficult anyway.) Australian author Haig introduces readers to a post-apocalyptic dystopia set far in the future, and in that sense it has more in common with Terry Brooks’s Shannara series or Robert S. Blum’s underrated ’80s book The Girl From the Emeraline Island. A few hundred years after nuclear war has scorched the earth, humanity has undergone a strange genetic variation. Every person is born a twin, one destined to be an Alpha (“perfect in every way,” to borrow a phrase from another Australian post-nuke story), and one destined to be an Omega (usually bearing a defect–six fingers, missing limbs, or the gift of psychic visions)–with one catch: when one twin dies, so does the other. No exceptions. The ruling Alphas impose all sorts of strictures on the Omegas, and in Fire Sermon, Omega seer Cass realizes her Alpha brother Zach’s plans to enslave all of the Omegas in order to ensure the well-being of the Alphas. I introduced V earlier because we can’t talk about The Fire Sermon–or even The Matrix, which I skipped because it borrows from V–without talking about them first; internment equals obliteration through enslavement–in short, the captive “others” have something the dominant invading culture wants or needs. And here be spoilers, so if you don’t want to know, skip to the next title. In V, the aliens came from a dying planet to take our water–and to store humans for food. In The Matrix, AIs have created a virtual reality to keep scores of captive humans from realizing that we’re kept as power sources for them. In The Fire Sermon, the very link between Alphas and Omegas–when one dies, the other does too–makes the Alphas perceive the Omegas as a threat that can only be controlled by being contained.

The Fire Sermon (2014), Francesca Haig (followed by The Map of Bones (2016) and The Forever Ship (2017). I liked The Fire Sermon because it was so different than some other dystopic science fiction fantasies I’ve read; for one thing, it does not drag in the middle, which I think is a weakness for many authors. (To be fair, middles are difficult anyway.) Australian author Haig introduces readers to a post-apocalyptic dystopia set far in the future, and in that sense it has more in common with Terry Brooks’s Shannara series or Robert S. Blum’s underrated ’80s book The Girl From the Emeraline Island. A few hundred years after nuclear war has scorched the earth, humanity has undergone a strange genetic variation. Every person is born a twin, one destined to be an Alpha (“perfect in every way,” to borrow a phrase from another Australian post-nuke story), and one destined to be an Omega (usually bearing a defect–six fingers, missing limbs, or the gift of psychic visions)–with one catch: when one twin dies, so does the other. No exceptions. The ruling Alphas impose all sorts of strictures on the Omegas, and in Fire Sermon, Omega seer Cass realizes her Alpha brother Zach’s plans to enslave all of the Omegas in order to ensure the well-being of the Alphas. I introduced V earlier because we can’t talk about The Fire Sermon–or even The Matrix, which I skipped because it borrows from V–without talking about them first; internment equals obliteration through enslavement–in short, the captive “others” have something the dominant invading culture wants or needs. And here be spoilers, so if you don’t want to know, skip to the next title. In V, the aliens came from a dying planet to take our water–and to store humans for food. In The Matrix, AIs have created a virtual reality to keep scores of captive humans from realizing that we’re kept as power sources for them. In The Fire Sermon, the very link between Alphas and Omegas–when one dies, the other does too–makes the Alphas perceive the Omegas as a threat that can only be controlled by being contained.

The Girl With All The Gifts, Mike Carey (2014; film, 2017). I discussed this excellent book in a previous Chain Reaction post. Internment is not a new theme in zombie stories, from Carrie Ryan’s The Forest of Hands and Teeth to The Walking Dead (e.g., The Governor’s and Negan’s storylines) and usually is focused on one or all of three tropes: keeping the humans in and the zombies out (which mostly fails miserably); using a mindless horde of zombies as borders, shields, or weapons; or both. What Carey does in TGWATG by (spoilers!) making the zombies sentient forces the reader to address the question, “Is this okay?” (My answer: No. It’s not okay when zombies are sentient, and it’s not okay when they’re mindless, either.) What Melanie and her classmates endure in TGWATG at the hands of what’s left of the British government is particularly cruel.

The Girl With All The Gifts, Mike Carey (2014; film, 2017). I discussed this excellent book in a previous Chain Reaction post. Internment is not a new theme in zombie stories, from Carrie Ryan’s The Forest of Hands and Teeth to The Walking Dead (e.g., The Governor’s and Negan’s storylines) and usually is focused on one or all of three tropes: keeping the humans in and the zombies out (which mostly fails miserably); using a mindless horde of zombies as borders, shields, or weapons; or both. What Carey does in TGWATG by (spoilers!) making the zombies sentient forces the reader to address the question, “Is this okay?” (My answer: No. It’s not okay when zombies are sentient, and it’s not okay when they’re mindless, either.) What Melanie and her classmates endure in TGWATG at the hands of what’s left of the British government is particularly cruel.

Hmm. Isn’t it strange that so many dystopias rely on incarceration of Others?

Last but not least:

The Event (2010-11). This TVseries lasted one season, but it, like District 9, presented an alternate history: a group of humanoid aliens crash-landed in the 1940s, and they were kept in a camp all that time until they escaped, and, led by Laura Innes, fresh off E.R., started affecting world order. No kidding. Except there were rival factions of aliens with different agendas–and then it was canceled, so we never got a proper middle.

Dark City (1998). This shouldn’t be any surprise given the ending. It is not just a wicked-weird, sci-fi/noir/supernatural murder mystery.

The Darkest Minds, Alexandra Bracken (2016; film, 2018). I haven’t read or seen this yet, so I don’t want to comment on it too much, except that the plot revolves around teenagers who survive an epidemic that kills off most other children–and those who survive develop fearsome abilities. The story follows a girl, Ruby, who has lived the last six years in a “rehabilitation center” where the government has placed any child with abilities.

Thanks for sticking with me. As I said before, wrongful incarceration or internment necessitates attention. If you have any other additions, please share them in the comments below.

I knew of the Japanese interment during WWII, but did not realize that there were several other instances that go largely ignored in American History. One book that addresses this is Charity Girl by Michael Lowenthal. During WWI, thousands of young women (some prostitutes, some not) were rounded up and forced into treatment facilities (i.e., prison homes) in order to stop the spread of what was called “social diseases” among the soldiers. Charity Girl takes this story and tells it from the point of view of a 17-year old girl who lives on her own in Boston. Having escaped the oppressive rule of her Russian-immigrant mother and the arranged marriage to an unappealing man more than twice her age, she is living on her own and enjoying the freedom that she has to go dancing or march in a parade with her friends. She meets the presumed man of her dreams, Felix, and experiences a day of firsts–first baseball game, first love, first time driving a car–only to have the world come crashing around her ears a few days later. She first loses her job, then is attacked by someone who says he can take her to see Felix, and is later found to be guilty of undermining the military authority and infecting a soldier (when in fact, Felix infected her) and suddenly is in a world that she has no control over. Humiliating body examinations, being put down by the house matron and other ‘residents’, etc. She is holding to the hope that she will find a way out, but there is little hope to be found.

It’s a hard read sometimes, and having a book such as this that relies so heavily on the female experience being written by a male can lead to some interesting perspectives. But it’s a blight on the history of our country, and one that deserves to have its story told.

Thanks for adding that. I looked it up and put it on my to-read list. The premise reminds me of last year’s “Miss Kopp” novel. Amy Stewart has fictionalized the adventures of the first female sheriff in the U.S., Constance Kopp (Kopp really was her name), and the third book, “Miss Kopp’s Midnight Confessions,” deals with a runaway sent to a reformatory. This is 1916, so just before WWI, but Stewart (who usually writes nonfiction) does a lot of thorough research, and the precedent for punishing “wayward girls” is evident. It’s a tangent to the storyline, but I recommend the Miss Kopp novels if you haven’t tried them yet.

I will certainly check them out!!!