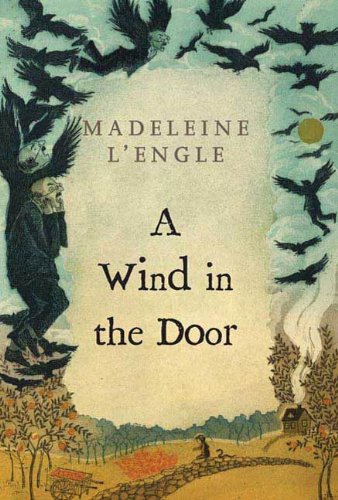

A Wind in the Door (1973)

A Wind in the Door (1973)

Written by: Madeleine L’Engle

Series: Time Quintet #2

Genre: Science Fantasy/Young Adult

Pages: 240 (Paperback)

Publisher: Macmillan

Why I Chose This: My 2018 Resolution Project for Speculative Chic was to read and review both the novel and film versions of A Wrinkle in Time. But I’m a completionist, so it should come as no surprise that I’d have to continue on this magical journey I somehow missed when I was a teenager.

The Premise:

A Wind in the Door is a fantastic adventure story involving Meg Murry, her small brother Charles Wallace, and Calvin O’Keefe, the chief characters of A Wrinkle in Time. The seed from which the story grows is a rather ordinary situation of Charles Wallace’s having difficulty in adapting to school. He is extremely bright, so much so that he gets punched around a lot for being “different”. He is also strangely, seriously ill (mitochondritis — the destruction of farandolae, minute creatures of the mitochondria in the blood). Determined to help Charles Wallace in school, Meg pays a visit to his principal, Mr. Jenkins, a dry, cold man with whom Meg herself has had unfortunate run-ins. The interview with Mr. Jenkins goes badly and Meg worriedly returns home to find Charles Wallace waiting for her. “There are,” he announces, “dragons in the twins’ vegetable garden. Or there were. They’ve moved to the north pasture now.”

Dragons? Not really, but an entity, a being stranger by far than dragons; and the encounter with this alien creature is only the first step that leads Meg, Calvin, and Mr. Jenkins out into galactic space, and then into the unimaginable small world of a mitochondrion. And, at last, safely, triumphantly, home.

No spoilers below!

Even though the film version of A Wrinkle in Time didn’t blow me a way, the casting was spot-on. Enough that from the very first paragraphs of this book, the fantastic actors from the film came alive for me once again in this new adventure. Which is good, because everything else about the beginning rather dragged on. Lots of asides, as if L’Engle wasn’t quite sure what story to write that would measure up to the achievements of A Wrinkle in Time. This was difficult for me as a reader, because I trust in Charles Wallace and know that he actually saw a dragon. While the added bits about break-ins in the village and vanishing stars became relevant later in the plot, I really just wanted to get back to potential dragons.

Finally, Meg Murry sets out to investigate her brother’s dragons, which is where the story truly begins. Alas, it’s not actually the sort of traditional dragon a Western reader might expect, because that’d be boring for the world L’Engle has created. Instead, L’Engle continues to blend mythological and religious imagery without telling an overtly religious tale. Charles Wallace’s dragon turns out to be a cherubim named Proginoskes, a creature of with too many wings and too many eyes, and honestly, the sort of dragon I’d probably prefer to find in a vegetable garden, too.

This novel followed a classic quest structure, as Meg and Progo are directed by an older advisor, the Teacher Blajeny, to undertake three trials. Meg continues her unfortunate trend of getting worked up and shouting about things a lot, but she’s also learned to get things done in the midst of it. Luckily, Calvin O’Keefe is once again along for the ride to be a steadying influence. The burgeoning romance here is delightfully subtle (“friend-friends”) without the usual YA trappings but I’d rather have explored that relationship more instead of being saddled by Charles Wallace’s principal. In typical YA novel fashion, some adults are supportive and competent, and some are dumb and boring. Mr Jenkins definitely falls into the latter camp, and I could have done without his participation in the second half of the tale.

This book had multiple layers of themes, from the limits of human adaptability to the definition of life. These are expanded upon with discussion about how they connect, and how everything connects — and affects — literally everything else. Despite the quest structure, the grand finale wasn’t about fighting a “big bad,” but about using these themes to overcome obstacles. Such a lesson is applicable to just about every conflict.

Despite these lessons, I didn’t necessarily feel that Meg grows as a character. Mostly, she flails about and stumbles into the answers she needs, but in the end, she’s never the one who makes any sacrifices. In retrospect, I’ve come to realize that Meg might be the protagonist of the book, but she’s not really the one here who’s supposed to learn anything, the “hero.” The reader — I am — instead.

In conclusion: I spent a lot of this novel wondering how it would transition to film, especially considering the many fantastical elements that extend far beyond cherubim. Unfortunately, the purely visual would not encompass how mental communication is presented and how all of the senses are wonderfully engaged through text alone. As the hero of this tale, I find that I’d much rather go back and savor certain scenes and passages as I wish for a cherubim of my own to befriend.

Featured image source: Wallpaper Abyss

No Comments