This month we put Changing the Map into the capable hands of writer and reviewer Ronya F. McCool for her discussion of Octavia E. Butler’s groundbreaking novel, Kindred. Part slave narrative, part time travel story, read on to see what Ronya has to say about how Kindred changed the map. –Sharon

When I was asked to write a review for this column, I leapt at the chance to review Kindred, because Octavia Butler, bless her soul, is one of my favorite writers. I knew Kindred was about slavery, and it is one of those books I really felt I should read; most importantly because the story was a witness to slavery, which is all too easily and heart-breakingly dismissed as “in the past,” and also because any discussion of Butler and her work would be spare and lean without it. But I was never able to get more than a few pages in anytime I tried to read it. To be honest, a few things in the opening pages jarred me, but I probably did not want to face the story because it was about slavery. Conversely I felt that this is why it was all the more necessary for me to read Kindred. What spurred me on is recent research that confirms traumatic stress can be genetically encoded down through generations, and that racial oppression, poverty, and inadequate access to health resources contributes to that traumatic stress (see also: pediatrician Dr. Nadine Burke Harris).

Kindred is about all of these things, and more. What Butler’s work did was teach me (again) what a powerful force relationships are to the human race.

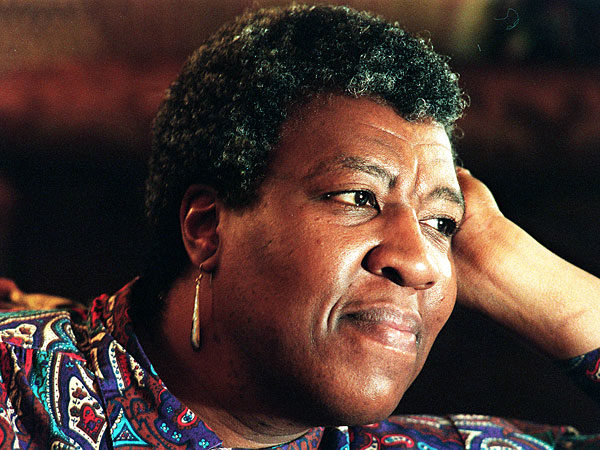

About the Author

Octavia E. Butler (1947 — 2006) was often referred to as the “grand dame of science fiction.” She is the first female African-American writer in the science fiction world. She was born in Pasadena, California, earned an Associate of Arts degree from Pasadena Community College, then studied at the Screenwriter’s Guild Open Door Program and the Clarion Science Fiction Writers’ Workshop. She twice won the Hugo Award, once the Nebula, and was awarded a MacArthur Foundation grant. She was posthumously inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame, and awarded the Solstice Award by Science Fiction Writers of America.

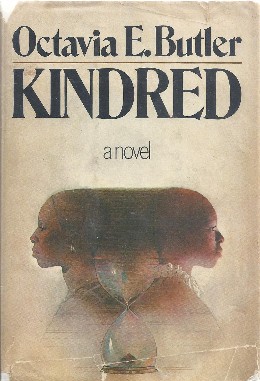

Kindred, published in 1979, was her fifth book, and just this January was adapted into a graphic novel.

Kindred (1979)

Kindred (1979)

Written by: Octavia E. Butler

Genre: Time Travel

Pages 264 (Trade Paperback)

Publisher: Beacon Press

Spoilers: Everything but the ending.

The Story: Beginning on her 26th birthday, Dana, a young Black writer in a happy, interracial marriage, is dragged backward in time from 1976 California to 1800s Maryland, where she discovers her purpose is to safeguard a boy named Rufus Weylin. Rufus, the son of Tom Weylin, a strict slave-owner, will grow up to father Dana’s ancestor, Hagar. Rufus is somehow able to call Dana whenever he is in a life-threatening situation; conversely, Dana can only return to 1976 when her own life is threatened. Only minutes or hours have passed in 1976, while months or years pass in 1800s Maryland. Dana, and later her husband Kevin, take it upon themselves to take advantage of the relationship they have formed with Rufus to try to guide him to be the gentle man that his father is not.

As I mentioned before, I’m a fan of Octavia Butler, but until now I had not read Kindred. Oh, I had tried. I couldn’t understand why I’d liked Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents and Butler’s short stories but Kindred put me off. I know I lost interest in it when the mechanism of time-travel wasn’t really explained, except to say the protagonist is called backward in time at the behest of her ancestor.

Years later, having read the entire thing in three hours flat, I see that is the entire point. Like the protagonist, Dana, the reader gets no say in being called back to 1800s Maryland. Dana and Kevin, and we along with them, are all simply hijacked from life in order to save Rufus — to ensure the well-being of a wealthy white boy who grows up to inherit a plantation.

There isn’t even a nice, tidy ending. And that is also the point. Kindred is nothing short of extraordinary, in a devastating, brutal kind of way. What Butler has done is to create a kind of corollary with slavery, so that its horrors can be witnessed (and in Dana’s case, experienced).

How It Changed The Map

Butler writes each character with complexity, lending nuance to the lives of slaves and time-travelers alike, rendering all of them as human. It’s not an easy thing to accomplish, but Octavia Butler is probably the only writer who could have done it. She grew up loving science fiction, unaware of the obstacles for a Black female writer, much less one who wanted to write science fiction.

Dana is the non-traditional heroine of this story (to say much more on that might give away the ending). Butler uses Dana as our eyes and ears, and therefore as our conduit, to the faults in the institution of slavery. In the 1970s, Dana is a temp worker; in Maryland, she “enjoys” a special kind of status because she is neither slave nor free. Realizing she cannot prove she is free, she chooses to work with the slaves. Tom Weylin grants her a special status as his son’s protector, since she has saved Rufus’s life so many times. Over the course of the story, Dana becomes concerned that her mission — to change Rufus as a person — is failing; so she tries to safeguard his person so he will be able to father her ancestor, Hagar. Even this presents a quandary: Rufus loves Alice, Hagar’s mother, but treats her as his property. When he tells Dana to influence Alice to come to his bedroom, Dana refuses. Instead she offers to help Alice escape.

Dana is the non-traditional heroine of this story (to say much more on that might give away the ending). Butler uses Dana as our eyes and ears, and therefore as our conduit, to the faults in the institution of slavery. In the 1970s, Dana is a temp worker; in Maryland, she “enjoys” a special kind of status because she is neither slave nor free. Realizing she cannot prove she is free, she chooses to work with the slaves. Tom Weylin grants her a special status as his son’s protector, since she has saved Rufus’s life so many times. Over the course of the story, Dana becomes concerned that her mission — to change Rufus as a person — is failing; so she tries to safeguard his person so he will be able to father her ancestor, Hagar. Even this presents a quandary: Rufus loves Alice, Hagar’s mother, but treats her as his property. When he tells Dana to influence Alice to come to his bedroom, Dana refuses. Instead she offers to help Alice escape.

What makes Kindred unique is that Butler also contrasts relationships to bare the injustices of slavery. There are three stable relationships in the novel. Dana herself is depicted as one-half of a loving, supportive couple. Dana and Kevin work together, which is not something readers normally see in stories. We are used to the sparring couple who won’t admit they’re in love; to “wimpy” men in relationships with “bitchy” women; to some sort of tension between two people in a relationship. After some initial resistance, however, Kevin does what he can both to support Dana and help her gain independence — or at least, foment her own sense of independence. Later Kevin travels back in time with Dana (and gets stuck there).

The only stable relationship amongst the slaves is that of young Carrie and Nigel, who are happy together and who were allowed a wedding ceremony. Nigel was allowed to work outside the plantation in order to build a house for his family.

Dana forges a friendship with Sarah, the cook, who teaches Dana how to cook and tells her how the plantation runs. It is the angry yet caring Sarah who tries to keep Dana from running away, Sarah who is the voice of what must pass for common sense on the Weylin plantation. She might easily be described as a “mammie” figure — but Rufus’s father sold three of her children and let her keep one to buy her complacency. As Dana says:

“She had done the safe thing — had accepted a life of slavery because she was afraid. She was the kind of woman who would be held in contempt during the militant nineteen sixties… the frightened, powerless woman who had already lost all she could stand to lose, and who knew as little about the freedom of the North as she knew about the hereafter.”

Dana too is accused by the others of serving at the Weylins’ beck and call, of kowtowing to the whites, but at another point, Alice, Tess, and Carrie — the friends she has made among the slave women — defend her by beating up another slave who interfered with Dana’s attempted escape from the Weylin household.

These relationships between Carrie and Nigel, Dana and Kevin, and Dana and Sarah, throw the injustices — whippings, rapes, physical and emotional abuse, the concept of owning humans as property, suicides — into sharp relief. Rufus’s relationship with his father is strained; his father cheats on his nervous, overbearing wife with slave women, and has children by them; Rufus grows up to do the same. The relationships between the slaves are strained, because of white interference. Sarah loses her children to the slave market; Nigel’s father is sold when he becomes too obstinate and stubborn. Isaac and Alice try to run away together, but are caught. Alice is brought home to Rufus while Isaac’s ears are cut off and he is sold south.

These relationships between Carrie and Nigel, Dana and Kevin, and Dana and Sarah, throw the injustices — whippings, rapes, physical and emotional abuse, the concept of owning humans as property, suicides — into sharp relief. Rufus’s relationship with his father is strained; his father cheats on his nervous, overbearing wife with slave women, and has children by them; Rufus grows up to do the same. The relationships between the slaves are strained, because of white interference. Sarah loses her children to the slave market; Nigel’s father is sold when he becomes too obstinate and stubborn. Isaac and Alice try to run away together, but are caught. Alice is brought home to Rufus while Isaac’s ears are cut off and he is sold south.

Dana and Kevin eventually both return to 1977 California; she is in effect another year older, having experienced a birthday while she was “away” in Maryland. She has lost an arm, and was the victim of whippings and beatings. Kevin has aged five years due to being stuck in 1800s Maryland and New York, where he worked to free slaves. They experience post-traumatic stress as they struggle to readjust to telephones, typewriters, and cars — and eventually travel to Maryland to try to find out what happened to the Weylin plantation.

Throughout the novel Butler rightly shies away from sensationalizing violence, which would have made this an altogether different book, but mined memoirs and slave narratives to present an uncompromising and brutal view of slavery as a pervasive institution that was used in overt and covert ways to control and dominate humans simply based on greed and skin color.

And maybe that is why I didn’t want to read it before.

The genius of Kindred is that it explores a variety of nuanced relationships to both bring to life a different time and more importantly expose slavery as a pervasive institution, in which people owned as slaves had no choice except to do whatever their masters wished. Butler reveals that every person has a story and personal motivations; something I know I would do well to remember. Through writing the novel, she seeks to correct notions about slavery, showing that being owned and surviving it, whatever form that survival took, was a courageous act. Butler never reduces a slave’s motivations to fate.

Although I think Kindred is more of a fantasy than a science fiction novel, given the strange time-travel mechanism that is only explained through psychic forces, I recommend Kindred to anyone who hasn’t yet read it. It feels as though it belongs on the same shelf as Frederick Douglass’s 1845 autobiographical work Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (writing as “Linda Brent” in 1861). Kindred was written forty years ago, but the story doesn’t lose any relevance. I’d argue that today its message of subverting institutions through forging strong interpersonal relationships is a necessary reminder of what it means to be human.

Although I think Kindred is more of a fantasy than a science fiction novel, given the strange time-travel mechanism that is only explained through psychic forces, I recommend Kindred to anyone who hasn’t yet read it. It feels as though it belongs on the same shelf as Frederick Douglass’s 1845 autobiographical work Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (writing as “Linda Brent” in 1861). Kindred was written forty years ago, but the story doesn’t lose any relevance. I’d argue that today its message of subverting institutions through forging strong interpersonal relationships is a necessary reminder of what it means to be human.

Often we look back on the past, and think of it as monolithic. We think of racism also as monolithic, and also obvious, things such as “I don’t believe in owning people, nor do I think people of different skin colors are inferior, so I am not racist.” And we think these things without questioning the smaller forces at work — of laws designed to target certain populations, for example. I’m guilty of all of that. But just because I’m not overtly racist doesn’t mean I’m not covertly racist. I’m learning, and I hope to continue to educate myself.

Like a few other Speculative Chic writers here, Ronya F. McCool is a graduate of the Odyssey Writing Workshop. She graduated from James Madison University in Virginia, and currently she is a librarian in St. Louis, Missouri, where she curates the science fiction and graphic novel collections, among other things. She is a master’s student in Alabama’s Library Studies program, focusing on issues of social justice and diversity.

Like a few other Speculative Chic writers here, Ronya F. McCool is a graduate of the Odyssey Writing Workshop. She graduated from James Madison University in Virginia, and currently she is a librarian in St. Louis, Missouri, where she curates the science fiction and graphic novel collections, among other things. She is a master’s student in Alabama’s Library Studies program, focusing on issues of social justice and diversity.

Next Month: Sharon is back to discuss Sherri Tepper’s classic sci-fi story of post-apocalyptic matriarchy, The Gate to Women’s Country.

This is a book that one day I mean to reread. The first time I read it, I remember my little writer brain kept having other expectations of the work based on my previous experience with Butler’s novels, so my experience was colored by what I expected the work to be rather than what it was. Now that I firmly know what the book IS, I can read it with that in mind. It’s not an easy read; it can be outright horrifying, but it’s no less satisfying because it of. It’s a fantastic gateway book to Butler’s fiction, and one I hope more people read, especially in this day and age.

Re: Ronya’s observations about relationships in this novel–that was one element that I felt was rather thin in the recently released graphic novel of Kindred. It’s always the case that something has to go when you boil a novel down to its graphical essence, but I did feel that was lost.

You know, the graphic novel may be just the way to “re-read” the material: a kind of fresh look while re-reading….

It certainly made the plantation scenes more intense